|

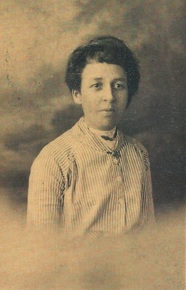

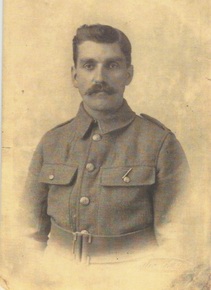

This week has seen the centenary of the commencement of World War One. It ended or changed millions of lives, including my grandparent's. He was a volunteer - a married man with three young children - when he joined up in 1915. Although serving as a Pioneer in the Royal Engineers on the western front until the end of the war, he was one of the lucky ones who came home. Seventeen million combatants and civilians died in the war. However, my grandfather's homecoming wasn't the one either he or his wife would have envisaged. Before he returned, she died in March 1919 from the Spanish 'flu pandemic which killed between 50-100 million people worldwide. There are millions of stories sadder or happier than this one. One good thing that will come from commemorating the centenary of World War One will be that more of these stories will come to light. Did members of your family serve during World War One? If so, leave a comment for me - I'd love to hear about them.

1 Comment

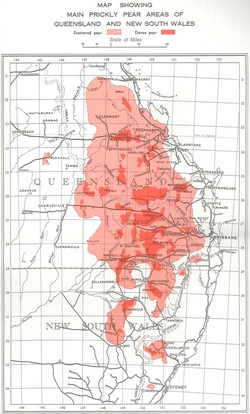

Source: A P Dodd, 1940. Source: A P Dodd, 1940. During the 1920s, the biggest concern for many people in country Queensland, aside from the weather, was the rapid spread of the pest cacti commonly known as prickly pear. From Mackay in central Queensland to central New South Wales, these plants were multiplying and choking the land. They had been introduced into Australia from North and South America during the nineteenth century. Warnings of their capacity to multiply and make good land useless began in the 1870s, but it wasn't until the 1890s that bylaws and legislation requiring their removal were created. By the early twentieth century, the need for a biological control of the pest had been recognised. Although an effective poison to kill the cacti was determined in 1916, obtaining it during World War One was difficult and Australia's manpower and the money to control prickly pear were employed overseas. Finally, in 1919, the Commonwealth Government and the governments of Queensland and New South Wales established a joint project, to discover and introduce into Australia biological pests of prickly pear, to control its spread. Achieving this goal was to take 10-20 years, but the introduction of Cactoblastis cactorum and a number of other parasites of the cacti, was an outstanding success. Not all of Queensland was affected by prickly pear. Open plains were generally spared the infestation - among them the plains of western Queensland. It is here that my latest book, All Quiet on the Western Plains is set. The characters therefore weren't involved in the struggle to control prickly pear that was going on in much of rural Queensland in 1924. Does your family have a story from the bad old days of Prickly Pear? I would love to hear from you. All Quiet on the Western Plains - available 1 May 2014 - from Amazon, Steam eReads and Book Srand. References: Dodd Alan P. The progress of biological control of prickly pear in Australia. Commonwealth Prickly Pear Board, Brisbane, 1929. Dodd Alan P. The biological campaign against prickly-pear. Commonwealth Prickly Pear Board, Brisbane, 1940. Dodd, Alan P. ‘The Conquest of Prickly-Pear’. RHSQJ, 1945, 3, 5, pp. 351-61. Mann, John. The Naturalised Cacti in Australia, Queensland Lands Department, Brisbane, 1970.  While working on my latest book, All Quiet on the Western Plains, I looked at fashions in the 1910s and '20s, and have since found some lovely French fashion studies from the period advertised online. They are from hand-painted pochoirs (stencils) - using gouache and watercolour - dating from circa 1912- circa 1925. I think the fashions are gorgeous! See what you think. Go to the following link, if you're interested (b.t.w. I have no connection to this business) : https://www.antiqueprintclub.com/c-23-fashionpochoir.aspx If you would like further information about pochoir and the journal in which they were published (Gazette Du Bon Ton - Mode et Frivolites) see: http://antique-print-club.blogspot.com.au/ |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed